The universe is a vast tapestry of cosmic wonders, and among its most intriguing mysteries is how planetary systems come into existence. ✨

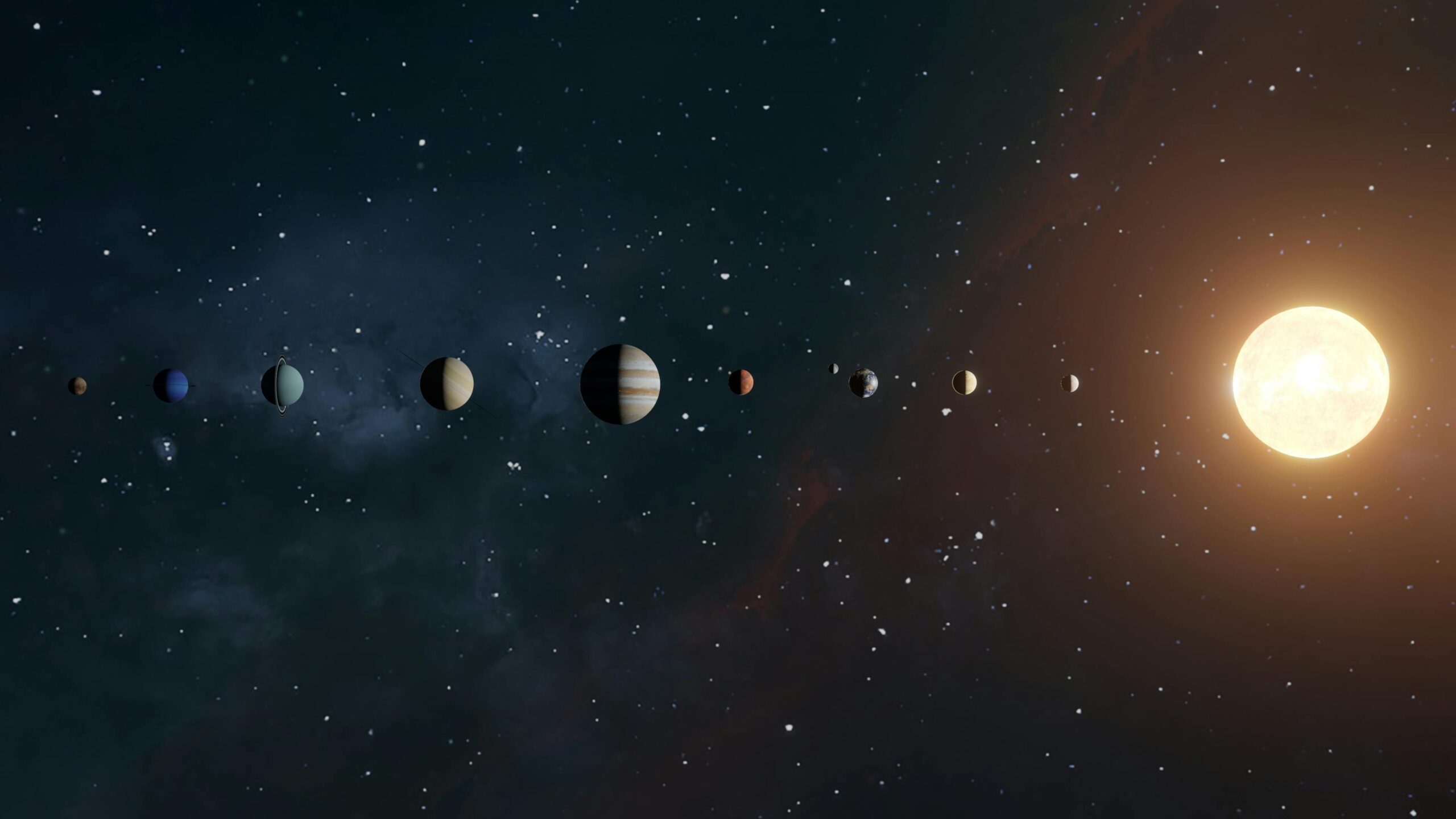

From swirling clouds of gas and dust to fully formed worlds orbiting distant stars, the formation of planetary systems represents one of the most spectacular transformations in the cosmos. Understanding this process not only helps us comprehend our own Solar System’s origins but also sheds light on the potential for life beyond Earth and the incredible diversity of exoplanetary systems discovered in recent decades.

🌌 The Cosmic Ingredients: What Makes Planetary Systems Possible

Before diving into the formation process itself, we must understand the fundamental building blocks that make planetary systems possible. The universe, following the Big Bang, was initially composed primarily of hydrogen and helium. However, successive generations of stars have enriched the cosmos with heavier elements through nuclear fusion and spectacular supernova explosions.

These heavier elements—carbon, oxygen, silicon, iron, and countless others—became the raw materials for planet formation. When combined with the abundant hydrogen and helium, these elements create the molecular clouds that serve as stellar nurseries throughout the galaxy. These enormous structures, sometimes spanning hundreds of light-years, contain enough material to form thousands of stars and their accompanying planetary systems.

The Role of Interstellar Medium

The interstellar medium plays a crucial role in setting the stage for planetary system formation. This diffuse matter between stars contains not only gas but also microscopic dust grains. These grains, though tiny, serve as crucial seeds for planet formation, providing surfaces where molecules can form and eventually contributing to the solid cores of planets.

The Nebular Hypothesis: A Framework for Understanding

The leading theory explaining planetary system formation is the nebular hypothesis, first proposed by Immanuel Kant and Pierre-Simon Laplace in the 18th century. Though refined significantly by modern astrophysics, the core concept remains remarkably relevant: planetary systems form from rotating clouds of gas and dust that collapse under their own gravity.

This elegant theory explains several key observations about our Solar System, including why planets orbit in roughly the same plane and why they all revolve in the same direction. The nebular hypothesis provides a coherent framework for understanding not just our own cosmic neighborhood but also the diverse array of exoplanetary systems discovered around other stars.

Modern Refinements and Observations

Today’s astronomers have access to powerful telescopes and instruments that allow direct observation of planetary systems in various stages of formation. Facilities like the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) have captured stunning images of protoplanetary disks around young stars, revealing gaps, rings, and asymmetries that indicate active planet formation occurring in real-time.

⭐ Stage One: Gravitational Collapse and Star Formation

The journey begins when a portion of a molecular cloud becomes unstable and begins to collapse. This instability might be triggered by various events: a nearby supernova shockwave, the collision of two clouds, or simply the cloud reaching a critical density threshold where gravity overcomes internal pressure.

As the cloud collapses, conservation of angular momentum causes it to spin faster, much like a figure skater pulling in their arms during a spin. This rotation causes the collapsing material to flatten into a disk structure—the protoplanetary disk—with a growing protostar forming at the center where material is densest and temperatures highest.

The Protostar Phase

During this phase, the central protostar continues accreting material from the surrounding disk while growing hotter and denser. Eventually, when temperatures and pressures in the core reach approximately 10 million degrees Celsius, hydrogen fusion ignites, and a true star is born. This process typically takes around 100,000 years for a Sun-like star, though it varies considerably depending on the star’s ultimate mass.

🪐 Stage Two: The Protoplanetary Disk Evolution

With the star now shining, the protoplanetary disk enters a critical phase for planet formation. The young star’s radiation heats the disk, creating temperature gradients that profoundly affect what types of planets can form at different distances. Close to the star, high temperatures vaporize volatile compounds like water ice, while in the cooler outer regions, these materials remain solid.

This temperature gradient creates what astronomers call the “frost line” or “snow line”—a boundary beyond which water and other volatiles can exist as ice. This boundary fundamentally determines the composition and characteristics of planets that form at different orbital distances.

Disk Composition and Dynamics

Protoplanetary disks are not static structures but dynamic environments where material constantly moves, collides, and evolves. Gas in the disk experiences friction and gradually spirals inward toward the star. Dust particles, however, can grow larger through collisions and eventually decouple from the gas, setting the stage for planet formation.

The Building Process: From Dust to Planetesimals

Planet formation begins at the smallest scales with microscopic dust grains. These particles, typically less than a micrometer in size, collide and stick together through electrostatic forces and molecular interactions. This process, called coagulation, gradually builds larger aggregates.

As these aggregates grow to millimeter and centimeter sizes, they face a significant challenge known as the “meter-size barrier.” At these sizes, aerodynamic drag from surrounding gas becomes highly efficient at causing objects to spiral into the star within just a few hundred orbits. Overcoming this barrier represents one of the key puzzles in planet formation theory.

Solutions to the Growth Challenge

Scientists have proposed several mechanisms to overcome the meter-size barrier:

- Turbulent concentration: Turbulence in the disk can concentrate particles into dense regions where they collide more frequently and grow faster

- Streaming instabilities: Under certain conditions, small particles can spontaneously clump together, rapidly forming much larger bodies

- Pressure bumps: Variations in disk pressure can trap particles, allowing them to accumulate and grow

- Planetesimal formation in vortices: Vortex structures in the disk can concentrate particles efficiently

🌍 Planetesimal to Planet: The Growth Continues

Once objects reach sizes of roughly one kilometer—called planetesimals—their own gravity becomes significant enough to attract additional material. This gravitational attraction dramatically accelerates growth through a process called runaway accretion. Larger planetesimals grow faster than smaller ones, quickly dominating their orbital zones.

Over millions of years, countless planetesimals collide and merge, forming progressively larger bodies called planetary embryos. These objects, ranging from Moon-sized to Mars-sized, represent the intermediate stage between planetesimals and fully formed planets.

Terrestrial Planet Formation

In the inner, warmer regions of the protoplanetary disk, where volatile ices cannot exist, planets form primarily from rocky and metallic materials. The formation of terrestrial planets like Earth, Venus, Mars, and Mercury involves violent collisions between planetary embryos over timescales of tens to hundreds of millions of years.

Computer simulations suggest that forming an Earth-like planet requires the collision and merger of perhaps a dozen or more Mars-sized embryos. These giant impacts generate tremendous heat, melting the growing planets and allowing denser materials like iron to sink toward the center, forming metallic cores surrounded by rocky mantles.

Gas Giant Genesis: A Different Path

Beyond the frost line, where temperatures are low enough for water ice and other volatiles to remain solid, planet formation takes a different course. The presence of ice dramatically increases the amount of solid material available, allowing planetary cores to grow much larger and faster than in the inner disk.

When a planetary core reaches approximately 10 Earth masses, its gravity becomes strong enough to capture and retain significant amounts of hydrogen and helium gas from the surrounding disk. This process, called gas accretion, can proceed extremely rapidly, building Jupiter-mass planets in just a few hundred thousand years once it begins.

The Core Accretion Model

The core accretion model describes gas giant formation as a two-stage process: first building a solid core through planetesimal accretion, then capturing a massive gaseous envelope. This model successfully explains many characteristics of Jupiter and Saturn but faces timing challenges, as protoplanetary disk gas typically dissipates within a few million years.

Alternative Formation Mechanisms

For the most massive gas giants and some exoplanets, an alternative formation mechanism called gravitational instability may play a role. In this scenario, dense regions of the protoplanetary disk become gravitationally unstable and directly collapse to form giant planet-mass objects without first building solid cores. This process could occur very rapidly, potentially within a few thousand years.

🔄 Migration: Planets on the Move

One of the most important discoveries in planetary system formation studies is that planets don’t necessarily remain where they form. Through gravitational interactions with the protoplanetary disk or with other planets, worlds can migrate substantially from their formation locations.

Several migration mechanisms have been identified:

- Type I migration: Affects low-mass planets embedded in gas-rich disks, typically causing inward migration

- Type II migration: Occurs when massive planets open gaps in the disk and migrate along with the viscously evolving gas

- Planet-planet scattering: Gravitational interactions between planets can dramatically alter orbits, sometimes ejecting planets entirely

- Kozai-Lidov mechanism: In systems with distant stellar or planetary companions, this effect can pump up orbital eccentricities and cause dramatic orbit changes

Hot Jupiters: Migration in Action

Perhaps the most dramatic evidence for planetary migration comes from “hot Jupiters”—gas giant planets orbiting extremely close to their host stars. These worlds couldn’t have formed in their current positions, where temperatures are far too high for ice to exist and build large cores. Instead, they must have formed in the outer system and migrated inward through disk interactions or gravitational scattering.

💫 The Final Architecture: Shaping Planetary Systems

As protoplanetary disks dissipate—typically within 3 to 10 million years—the era of rapid planet formation draws to a close. However, the story doesn’t end there. Young planetary systems continue evolving through gravitational interactions, collisions, and orbital rearrangements for hundreds of millions of years.

This late-stage evolution can dramatically reshape planetary system architecture. In our Solar System, the “Late Heavy Bombardment” approximately 4 billion years ago may have resulted from a major reorganization of the giant planets’ orbits, triggering a cascade of collisions throughout the inner Solar System.

Debris Disks and Late Accretion

Even after the main phase of planet formation concludes, leftover planetesimals form debris disks that can persist for billions of years. These disks, analogous to our Solar System’s asteroid and Kuiper belts, occasionally deliver material to planets through impacts. Such late accretion may have been crucial for delivering water and organic compounds to Earth, potentially playing a role in life’s emergence.

🔭 Exoplanetary Systems: Expanding Our Understanding

Since the first exoplanet discoveries in the 1990s, astronomers have detected thousands of planets orbiting other stars. These discoveries have revolutionized our understanding of planetary system formation by revealing a stunning diversity of system architectures that challenge and extend formation theories developed primarily from studying our Solar System.

We’ve discovered systems with multiple planets orbiting closer to their star than Mercury orbits the Sun, massive planets on extremely elliptical orbits, worlds orbiting binary stars, and planetary systems around pulsars—dead stellar remnants. Each discovery provides new constraints and insights into the planet formation process.

Lessons from Exoplanet Diversity

The incredible variety of exoplanetary systems reveals that planetary system formation is a robust but flexible process. The same fundamental physics operates everywhere, but initial conditions and random events during formation can lead to vastly different outcomes. This understanding has important implications for assessing how common Earth-like planets and potentially habitable environments might be throughout the galaxy.

The Search for Life: Formation’s Ultimate Question

Understanding planetary system formation connects directly to humanity’s search for life beyond Earth. The formation process determines which stars host planets, what types of planets form, where habitable zones exist, and how volatile compounds like water get delivered to terrestrial worlds—all crucial factors in assessing a planet’s potential habitability.

Recent discoveries of potentially habitable exoplanets, including several orbiting within their stars’ habitable zones, have energized this search. Future missions and telescopes will scrutinize these worlds’ atmospheres, searching for biosignatures that might indicate life has taken hold elsewhere in the cosmos.

Looking Forward: Unanswered Questions and Future Discoveries

Despite tremendous progress, many fundamental questions about planetary system formation remain unanswered. How exactly do particles overcome growth barriers? What determines the final masses and compositions of planets? How common are Earth-like worlds? Can life emerge in exotic planetary environments unlike anything in our Solar System?

Next-generation telescopes and instruments promise to address these questions. The James Webb Space Telescope is already revealing unprecedented details of protoplanetary disks and exoplanet atmospheres. Future missions will directly image young planets during formation and characterize potentially habitable worlds with extraordinary precision.

🌟 The Cosmic Perspective: Our Place in the Universe

Studying planetary system formation provides profound perspective on humanity’s place in the universe. We’ve learned that we inhabit an ordinary planet orbiting an ordinary star in a galaxy filled with billions of other planetary systems. Yet the specific circumstances of our Solar System’s formation—the particular arrangement of planets, the delivery of water to Earth, the stabilizing presence of Jupiter, and countless other factors—created the unique conditions that allowed life to flourish.

Every planetary system represents a unique experiment in cosmic evolution, shaped by physics, chemistry, and chance. From swirling clouds of gas and dust emerge worlds of incredible diversity: scorching infernos, frozen ice giants, rocky terrestrial planets, and perhaps, scattered throughout the cosmos, other worlds where life has emerged to contemplate its own origins.

The formation of planetary systems stands as one of nature’s most magnificent transformations—a process that converts diffuse interstellar clouds into structured systems of diverse worlds. As we continue exploring this fascinating journey, each discovery brings us closer to understanding not only how planets form but also our own cosmic origins and the possibility that we share the universe with other living worlds. The quest to unveil these cosmic origins continues, driven by human curiosity and our deep desire to understand the universe we call home.

Toni Santos is a science storyteller and space culture researcher exploring how astronomy, philosophy, and technology reveal humanity’s place in the cosmos. Through his work, Toni examines the cultural, ethical, and emotional dimensions of exploration — from ancient stargazing to modern astrobiology. Fascinated by the intersection of discovery and meaning, he studies how science transforms imagination into knowledge, and how the quest to understand the universe also deepens our understanding of ourselves. Combining space history, ethics, and narrative research, Toni’s writing bridges science and reflection — illuminating how curiosity shapes both progress and wonder. His work is a tribute to: The human desire to explore and understand the unknown The ethical responsibility of discovery beyond Earth The poetic balance between science, imagination, and awe Whether you are passionate about astrobiology, planetary science, or the philosophy of exploration, Toni invites you to journey through the stars — one question, one discovery, one story at a time.