The universe is vast, mysterious, and filled with countless worlds waiting to be understood. Comparative planetology offers us a unique lens through which we can examine these distant realms, drawing parallels and contrasts that illuminate not only alien worlds but also deepen our understanding of our own planet Earth.

By studying the similarities and differences between planetary bodies—from our neighboring planets Mars and Venus to the thousands of exoplanets discovered beyond our solar system—scientists are piecing together a comprehensive narrative of how planets form, evolve, and potentially harbor life. This comparative approach has revolutionized our understanding of planetary science and continues to unlock secrets that were once thought forever beyond our reach.

🌍 The Foundation: Understanding Earth Through Comparative Eyes

Earth serves as our reference point, the only planet we know intimately. Its dynamic atmosphere, protective magnetic field, active plate tectonics, and abundant liquid water make it unique in our solar system. However, understanding what makes Earth special requires examining what it shares with other worlds and what sets it apart.

Our planet’s atmosphere, composed primarily of nitrogen and oxygen, sustains a delicate balance that maintains temperatures suitable for liquid water. The presence of a strong magnetic field shields us from harmful solar radiation, while plate tectonics continuously recycle materials and regulate atmospheric composition over geological timescales.

These characteristics become even more remarkable when compared to our planetary neighbors. Earth occupies what astronomers call the “habitable zone”—the region around a star where conditions might allow liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. But being in this zone is just one factor among many that contribute to habitability.

🔴 Mars: The Red Planet’s Tale of Lost Potential

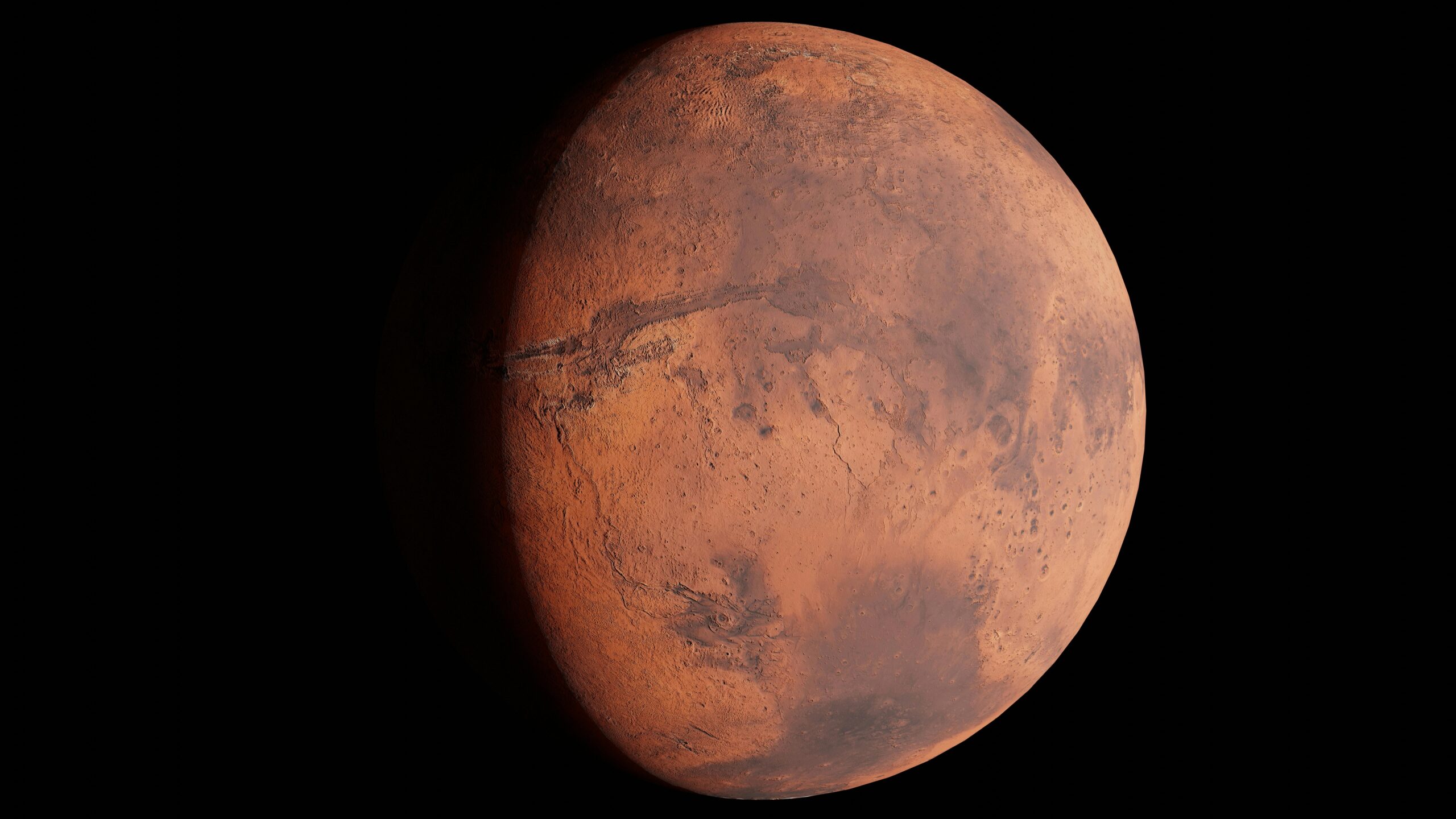

Mars stands as perhaps the most studied planet beyond Earth, and for good reason. This rusty world offers tantalizing clues about what happens when a planet loses its protective mechanisms. Comparative planetology reveals Mars as a cautionary tale—a world that may have once resembled Earth but took a dramatically different evolutionary path.

Ancient Mars: A Wetter, Warmer World

Evidence gathered from orbital missions and surface rovers paints a picture of ancient Mars that would be almost unrecognizable today. Dry riverbeds, ancient lake deposits, and minerals that form only in the presence of water suggest that Mars once possessed a thicker atmosphere and liquid water on its surface billions of years ago.

The planet’s smaller size proved to be its downfall. With only about half Earth’s radius and roughly one-tenth its mass, Mars cooled more rapidly. Its liquid iron core solidified, shutting down the planetary dynamo that once generated a protective magnetic field. Without this shield, solar wind gradually stripped away much of the Martian atmosphere over billions of years.

Modern Mars: Lessons in Planetary Evolution

Today’s Mars is a frozen desert with an atmosphere just 1% as thick as Earth’s. Surface temperatures average around -80°F (-62°C), and any liquid water would quickly freeze or evaporate. Yet Mars continues to surprise us with discoveries of subsurface ice, seasonal methane releases, and possible briny water flows.

These findings inform our understanding of planetary habitability limits. Mars demonstrates that past habitability doesn’t guarantee present conditions, and that planetary size and geological activity play crucial roles in maintaining life-supporting environments over geological timescales.

♀️ Venus: Earth’s Twisted Twin

If Mars represents lost potential, Venus embodies environmental catastrophe. Often called Earth’s twin due to similar size and mass, Venus is anything but hospitable. Its surface temperature of 900°F (475°C) is hot enough to melt lead, and its atmospheric pressure is 90 times that of Earth—equivalent to being nearly a kilometer underwater.

The Runaway Greenhouse Effect

Venus provides the most dramatic example of a runaway greenhouse effect in our solar system. Its thick atmosphere, composed of 96% carbon dioxide with clouds of sulfuric acid, traps heat so effectively that Venus is actually hotter than Mercury, despite being nearly twice as far from the Sun.

Scientists theorize that Venus may have once possessed oceans like Earth. However, its slightly closer proximity to the Sun may have triggered a feedback loop: increased solar heating evaporated more water, and since water vapor is itself a greenhouse gas, this caused more warming, which evaporated more water, continuing until the oceans were gone and the planet transformed into the hellish world we observe today.

Comparative Insights on Climate Stability

Venus serves as a stark warning about climate tipping points and the importance of negative feedback mechanisms. Earth’s carbon cycle, involving plate tectonics, weathering, and ocean chemistry, helps regulate our planet’s temperature over long timescales. Venus, which shows no evidence of plate tectonics, lacks this crucial regulatory system.

The study of Venus has profound implications for understanding climate change on Earth and identifying potentially habitable exoplanets. It demonstrates that being in the habitable zone isn’t enough—planetary characteristics like atmospheric composition, geological activity, and distance from the host star all interact in complex ways.

🌌 Exoplanetary Twins: A Universe of Possibilities

The discovery of thousands of exoplanets—planets orbiting stars beyond our Sun—has revolutionized comparative planetology. These distant worlds come in astonishing varieties, many unlike anything in our solar system, while others bear striking resemblances to planets we know.

Hot Jupiters and Super-Earths

Early exoplanet discoveries challenged our understanding of planetary system formation. Hot Jupiters—gas giants orbiting extremely close to their parent stars—were completely unexpected. These planets likely formed farther out in their systems and migrated inward, a process that has forced scientists to revise theories of planetary formation.

Super-Earths, planets larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune, represent the most common type of exoplanet discovered so far. Ironically, our solar system lacks this category entirely. These worlds range from rocky super-Earths that might be scaled-up versions of our planet to mini-Neptunes with thick hydrogen atmospheres.

Finding Earth’s True Twins

The search for Earth-like exoplanets drives much of modern astronomy. Astronomers look for planets with specific characteristics: similar size to Earth, rocky composition, location in the habitable zone, and orbiting stable, Sun-like stars. Several promising candidates have been identified, including planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system, Proxima Centauri b, and Kepler-452b.

However, comparative planetology teaches us that surface conditions depend on much more than just size and stellar distance. Atmospheric composition, magnetic field presence, geological activity, and stellar characteristics all play crucial roles in determining whether a planet could support life as we know it.

🔬 Methods and Tools of Comparative Planetology

Modern comparative planetology employs an impressive array of tools and techniques to study planetary bodies across the cosmos. Each method provides unique insights that contribute to our comprehensive understanding of planetary systems.

Spacecraft Missions and Remote Sensing

Direct exploration through spacecraft remains invaluable for studying planets in our solar system. Orbiters can map surface features, measure atmospheric composition, and detect magnetic fields. Landers and rovers provide ground-truth data, analyzing rocks, measuring weather, and searching for signs of past or present life.

Recent missions like NASA’s Perseverance rover on Mars and the planned Europa Clipper mission to Jupiter’s ice-covered moon demonstrate continued commitment to in-situ exploration. These missions provide data that simply cannot be obtained through telescopic observation alone.

Exoplanet Detection and Characterization

For exoplanets, astronomers employ indirect detection methods. The transit method measures the tiny dimming of a star’s light as a planet passes in front of it, revealing the planet’s size and orbital period. The radial velocity method detects the wobble a planet induces in its host star, providing information about the planet’s mass.

Newer techniques like transmission spectroscopy allow scientists to analyze exoplanet atmospheres by studying starlight filtered through them during transits. This method has detected water vapor, methane, and other molecules in exoplanetary atmospheres, bringing us closer to characterizing these distant worlds.

🧬 The Search for Life Through Comparative Analysis

Perhaps the most compelling application of comparative planetology is in astrobiology—the search for life beyond Earth. By understanding the conditions that allowed life to arise and thrive on Earth, and comparing them to other worlds, scientists can identify the most promising targets in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Biosignatures and Habitability Markers

Earth’s atmosphere contains oxygen in large quantities primarily because of photosynthetic life. This biosignature—a substance or phenomenon that provides scientific evidence of life—could potentially be detected in exoplanet atmospheres. Other potential biosignatures include methane in combination with oxygen, or certain organic molecules.

However, comparative planetology warns against jumping to conclusions. Mars produces methane through geological processes, and Venus’s clouds contain phosphine, which some scientists initially suggested might indicate life. These examples demonstrate the importance of understanding abiotic (non-biological) processes that might mimic biosignatures.

Expanding Our Definition of Habitability

Studying extreme environments on Earth—from deep-sea hydrothermal vents to Antarctic subglacial lakes—has expanded our concept of where life might exist. Comparative planetology applies these insights to other worlds, suggesting that subsurface oceans on moons like Europa and Enceladus might harbor life, even though their surfaces are frozen and hostile.

This broader view of habitability influences how we prioritize targets for future missions and direct our search for life beyond Earth. It reminds us that life might not only exist in Earth-like conditions but could adapt to environments we’re only beginning to understand.

🚀 Future Frontiers in Comparative Planetology

The field of comparative planetology stands at an exciting threshold. Next-generation telescopes, improved spacecraft technology, and advanced analytical methods promise to revolutionize our understanding of planets across the universe.

Next-Generation Space Telescopes

The James Webb Space Telescope has already begun providing unprecedented views of exoplanet atmospheres with its infrared capabilities. Future missions like the proposed LUVOIR (Large UV/Optical/IR Surveyor) and HabEx (Habitable Exoplanet Observatory) could directly image Earth-like exoplanets and analyze their atmospheres for biosignatures.

These advanced observatories will allow astronomers to conduct detailed comparative studies of exoplanetary atmospheres, searching for combinations of gases that might indicate biological processes and studying how different planetary environments evolve over time.

Sample Return Missions

Future sample return missions to Mars, and potentially to Venus’s atmosphere and the moons of the outer solar system, will bring extraterrestrial material to Earth’s laboratories for detailed analysis. These samples will provide insights impossible to obtain with remote instruments, potentially answering fundamental questions about planetary formation, evolution, and habitability.

The Mars Sample Return mission, a collaboration between NASA and ESA, aims to bring Martian rocks and soil to Earth by the early 2030s. These samples could contain evidence of past microbial life or provide definitive answers about Mars’s geological and climatic history.

🌟 Synthesizing Knowledge Across Worlds

Comparative planetology reminds us that no planet exists in isolation. Each world tells part of a larger story about how planetary systems form, evolve, and interact with their host stars. By studying the full diversity of planets—from the scorched surface of Venus to frozen Martian polar caps to exotic exoplanets in distant star systems—we gain perspective on Earth’s place in the cosmos.

This comparative approach has practical applications beyond pure science. Understanding how planetary climates can undergo dramatic transitions informs our response to climate change on Earth. Studying how Mars lost its atmosphere helps us appreciate the protective mechanisms that maintain Earth’s habitability. Examining Venus’s runaway greenhouse effect provides a cautionary tale about the consequences of atmospheric changes.

As we continue to discover and characterize exoplanets, we’re building a comprehensive framework for understanding planetary diversity. Some exoplanets resemble worlds in our solar system, while others represent entirely new categories that challenge our theories. Each discovery refines our understanding of what makes planets habitable and where we should focus our search for life beyond Earth.

The journey of comparative planetology is far from complete. With each new mission, telescope, and discovery, we add pieces to an enormous cosmic puzzle. These worlds beyond our own—Mars with its ancient river valleys, Venus with its crushing atmosphere, and countless exoplanets orbiting distant stars—all contribute to humanity’s quest to understand our place in the universe and answer the profound question: are we alone?

Through the lens of comparative planetology, we see not just distant worlds but reflections of possibilities—what Earth might have been, what it could become, and what other worlds might harbor conditions suitable for life. This perspective transforms astronomy from merely cataloging celestial objects into understanding the fundamental processes that shape worlds across the cosmos, bringing us closer to answering humanity’s oldest questions about our origins and our cosmic neighbors.

Toni Santos is a science storyteller and space culture researcher exploring how astronomy, philosophy, and technology reveal humanity’s place in the cosmos. Through his work, Toni examines the cultural, ethical, and emotional dimensions of exploration — from ancient stargazing to modern astrobiology. Fascinated by the intersection of discovery and meaning, he studies how science transforms imagination into knowledge, and how the quest to understand the universe also deepens our understanding of ourselves. Combining space history, ethics, and narrative research, Toni’s writing bridges science and reflection — illuminating how curiosity shapes both progress and wonder. His work is a tribute to: The human desire to explore and understand the unknown The ethical responsibility of discovery beyond Earth The poetic balance between science, imagination, and awe Whether you are passionate about astrobiology, planetary science, or the philosophy of exploration, Toni invites you to journey through the stars — one question, one discovery, one story at a time.